Diagnosis

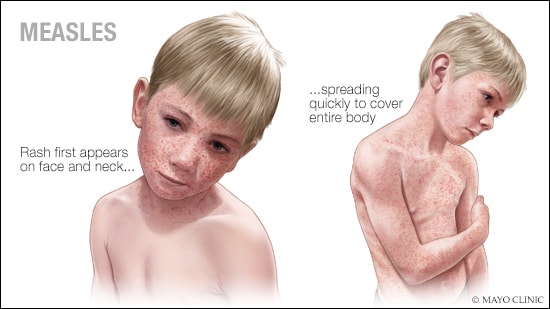

Your health care provider can usually diagnose measles based on the disease's characteristic rash as well as a small, bluish-white spot on a bright red background — Koplik's spot — on the inside lining of the cheek. Your provider may ask about whether you or your child has received measles vaccines, whether you have traveled internationally outside of the U.S. recently, and if you've had contact with anyone who has a rash or fever.

However, many providers have never seen measles. The rash can be confused with many other illnesses, too. If necessary, a blood test can confirm whether the rash is measles. The measles virus can also be confirmed with a test that generally uses a throat swab or urine sample.

Treatment

There's no specific treatment for a measles infection once it occurs. Treatment includes providing comfort measures to relieve symptoms, such as rest, and treating or preventing complications.

However, some measures can be taken to protect individuals who don't have immunity to measles after they've been exposed to the virus.

- Post-exposure vaccination. People without immunity to measles, including infants, may be given the measles vaccine within 72 hours of exposure to the measles virus to provide protection against it. If measles still develops, it usually has milder symptoms and lasts for a shorter time.

- Immune serum globulin. Pregnant women, infants and people with weakened immune systems who are exposed to the virus may receive an injection of proteins (antibodies) called immune serum globulin. When given within six days of exposure to the virus, these antibodies can prevent measles or make symptoms less severe.

Medications

Treatment for a measles infection may include:

Fever reducers. If a fever is making you or your child uncomfortable, you can use over-the-counter medications such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, Children's Motrin, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve) to help bring down the fever that accompanies measles. Read the labels carefully or ask your health care provider or pharmacist about the appropriate dose.

Use caution when giving aspirin to children or teenagers. Though aspirin is approved for use in children older than age 3, children and teenagers recovering from chickenpox or flu-like symptoms should never take aspirin. This is because aspirin has been linked to Reye's syndrome, a rare but potentially life-threatening condition, in such children.

- Antibiotics. If a bacterial infection, such as pneumonia or an ear infection, develops while you or your child has measles, your health care provider may prescribe an antibiotic.

- Vitamin A. Children with low levels of vitamin A are more likely to have a more severe case of measles. Giving a child vitamin A may lessen the severity of measles infection. It's generally given as a large dose of 200,000 international units (IU) for children older than a year. Smaller doses may be given to younger children.

Self care

If you or your child has measles, keep in touch with your health care provider as you monitor the progress of the disease and watch for complications. Also try these comfort measures:

- Take it easy. Get rest and avoid busy activities.

- Drink plenty of fluids. Drink plenty of water, fruit juice and herbal tea to replace fluids lost by fever and sweating. If needed, you can buy rehydration solutions without a prescription. These solutions contain water and salts in specific proportions to replace both fluids and electrolytes.

- Moisten the air. Use a humidifier to relieve a cough and sore throat. Adding moisture to the air can help ease discomfort. Choose a cool-mist humidifier and clean it daily because bacteria and molds can flourish in some humidifiers.

- Moisten your nose. Saline nasal sprays can soothe irritation by keeping the inside of the nose moist.

- Rest your eyes. If you or your child finds bright light irritating, as do many people with measles, keep the lights low or wear sunglasses. Also avoid reading or watching television if light from a reading lamp or from the television is bothersome.

Preparing for your appointment

If you suspect that you or your child has measles, you need to contact your health care provider. When you check in for the appointment, be sure to tell the check-in desk that you suspect an infectious disease. You and your child may be asked to wear a face mask or shown to an exam room immediately.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any symptoms you or your child is experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for which you scheduled the appointment.

- Key personal information, including any recent travel or contact with someone who was sick.

- All medications, vitamins or supplements that you or your child is taking.

- Questions to ask your health care provider.

Some basic questions to ask include:

- What's the most likely cause of my or my child's symptoms?

- Are there other possible causes?

- What treatments are available, and which do you recommend?

- Is there anything I can do to make my child more comfortable?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can take with me? What websites do you recommend?

What to expect from your doctor

Your health care provider may ask that you come in before or after office hours to reduce the risk of exposing others to measles. In addition, if the provider believes that you or your child has measles, the provider must report those findings to the local health department.

Your provider is likely to ask you a number of questions, such as:

- Have you or your child been vaccinated against measles? If so, do you know when?

- Have you traveled out of the U.S. recently?

- Does anyone else live in your household? If yes, have they been vaccinated against measles?

What you can do in the meantime

While you're waiting to see the health care provider:

- Stay well hydrated

- Bring a fever down safely

- Isolate from others